Nascar Versus The World

Evil track cars and the nature of intimidation, wrapped in a good ol’ test of hometown boy against everybody.

WE WANTED TO GET SPOOKED.

It began with an R&T staff bull session in a paddock somewhere. Somebody pointed out that no one ever complains about a car that’s easy to drive. And yet car people tend to rail against the “wrong” kind of progress: complexity, high curb weights, computers doing all the work.

ON THAT NOTE, in the interest of science, we gathered a few famously hairy modern machines. First, a NASCAR stocker set up for track days, because stock cars are purposely simple and occasionally mocked for it. Next, we added three carefully selected vehicles, different in blueprint and widely loved for their demanding nature: an iconic American bruiser, an all-wheel-drive Japanese behemoth, and a bare-bones Euro track special. Finally, we threw in a club-racer editor of moderate talent (yours truly) and a young NASCAR pro with a road-racing background but few sponsor ties. (Translation on that last one: no manufacturer obligations, and uncensored, trustworthy opinions.)

The pro is 28-year-old friend of R&T Parker Kligerman. Kligerman brought us one of his team’s cars, a Toyota Camry nearly identical to those in the 2019 NASCAR Monster Energy Cup. And then we looked at just what it takes to make these machines work, in spite—or perhaps because—of their reputations.

Since the human brain can get used to almost anything, first impressions were key: Kligerman ran his timed laps with purposely little practice, so his data would reflect a car’s approachability.

Is intimidation all it’s cracked up to be? Are fast cars better when they’re out for blood? We shone a light in the dark and learned a bit. (And then we did donuts in a stock car, because, well, who wouldn’t?)

2019 Nissan GT-R Nismo

PLACE OF ORIGIN: Japan, Land of Mythical Monsters

LAYOUT: Front-engine, all-wheel drive; 3.8-liter twin-turbo V-6, 600 hp, 418 lb-ft; 6-speed twin-clutch automatic

WEIGHT: 3900 lb

0–60 MPH: 2.9 seconds

¼-MILE: 11.1 seconds @ 125.9 mph

PRICE: $177,235 base, $178,655 as tested

NICKNAME GIVEN BY CAR PEOPLE: Godzilla

THE BLUEPRINT: An ancient platform, first sold in America in 2008. A curb weight so high, it looks like a typo. A quiet cabin and a turbocharged V-6 known for swallowing huge boost in the aftermarket. Plus digitally managed differentials engineered at a time when that technology was as common in America as squid jerky. (Pro tip: sold in Tokyo 7-Eleven stores. Tastes like rubber sea beef but is also somehow great. Try it.)

WHAT YOU GET: Nismo stands for Nissan Motorsport, the company’s multifaceted performance division; they have made hop-up parts for CUVs, and they have built prototypes for Le Mans. The Nismo GT-R is some of their finest work. Call it the last of the first of the modern Japanese speed titans, now with a heart-stopping price tag—$77,245 over the base GT-R!—and more gnarly track focus. The ordinary GT-R is a visceral icon; the Nismo version deletes rear seats but adds 35 hp, some carbon panels and trim, and a more neutral, playful state of chassis tune. If that’s not enough, you get 14-year-old kids cheering you on from sidewalks.

WHAT IT WANTS: Eleven years ago, when the earth was still cooling and the GT-R was new, the Nissan felt like a digital simulacrum of a real car. Now that virtually everything on the market is heavy and electronically watchdogged, the Nismo seems like a relic from a simpler time, a breath of fresh air. Some of the happiness here is simple engineering; the GT-R’s feel and balance have been improved over the years. Some of it is just a lack of progress: hydraulic steering, for example, has mostly been replaced by more distant electrically assisted racks. The Nissan’s ancient hydro unit is alive with nibbles of feedback.

Corners are a matter of getting the heavy nose settled on its relatively soft springs, pivoting the car on a deep brake application, and waiting for the front tires to make nice with the pavement. Once that happens, you mat the throttle and watch landscape smear. The delicious torque smack never quite jibes with the weight—nothing this heavy should feel as much like a ball of energy or be able to move as much earth from low speed. It feels like cheating.

Not that the Nissan is welcoming. You’re still dealing with serious hardware, a rear-biased all-wheel-drive car with 600 hp. The dusting of turbo lag on big throttle changes can take a lap or three to learn to exploit, and the abrupt throttle tip-in can be annoying. Managing the Nismo’s rear roll stiffness and unlock-happy diffs on entry requires quick hands and comfort with slides. The brake pedal is also surprisingly soft and long, and its travel and bite can change lap by lap. All of which means you occasionally have to stop being old-school gentle and just grab the car by the scruff.

But that’s the best part: it’s alive. You climb into a machine like this wondering if anything so fat and old could live up to the legend. Then the rear tires spit loose out of a corner and you’re just happy Godzilla is still around, still heavy and complex, still fudging the laws of nature.

THE PRO SAID: “It dances. It’s huckable. It hooks up so well that you forget the weight for a second and have to remind yourself to not destroy the outside front tire. You’re like, come on, rotate, and it just won’t. There are moments—110, 120 mph—where it wallows and you can’t commit back to throttle. That’s just weight and tire. But it’s the most approachable thing here. I let it wiggle around more; I feel more comfortable catching it.

“It’s fun! Reminds me of all-wheel-drive Subarus or a Ford Focus RS: in a highspeed corner, you touch the throttle, you can get the front end to go out and come back in, as the diff works.”

INTIMIDATING? Only if you’re not paying attention. Otherwise, it’s a kitten.

WHO BUYS IT? Large-pectoraled individuals with an affinity for pomade. Blessed otaku who dedicate an entire room in their house to 1:43-scale R34 GT-R models in race liveries. Clear-eyed problem solvers.

2019 Chevrolet Corvette ZR1

PLACE OF ORIGIN: Detroit, Sovereign Kingdom of Engines

LAYOUT: Front-engine, rear-wheel drive; 6.2-liter supercharged V-8, 755 hp, 715 lb-ft; 8-speed torque-converter automatic

WEIGHT: 3671 lb

0–60 MPH: 3.1 seconds

¼-MILE: 11.1 seconds @ 129.1 mph

PRICE: $124,095 base

NICKNAMES GIVEN BY R&T STAFF: Plastic Fantastic, Chest-Hair Charlie, Is That a Hood Scoop or Are You Just Happy to See Me?

THE BLUEPRINT: The only mass-production American sports car we have left. A badge that won Le Mans. Steel backbone frame, composite panels, a supercharged V-8 with an available clutch pedal. (Our test car featured the optional and clunky eight-speed automatic, boo hiss.) In 755-hp ZR1 form, you get enough track prowess to run with the world-beating, 690-hp Porsche 911 GT2 RS, but for less than half the Porsche’s sticker. Freedom on the hoof.

WHAT YOU GET: There are Corvettes, and then there are Corvettes. Buy a ZR1, you drive off the lot with one of the chest-hairiest machines in history. The Eaton blower under that comically engorged hood houses rotors the size of a city bus. It helps produce a barbaric noise and explosive torque that can smack the car sideways well above highway speed. Our test car wore the optional Track Performance package—a $2995 extra that includes Michelin Pilot Sport Cup 2 R-compound tires, a more focused suspension calibration, a more effective rear wing, and downforce-happy end caps for the front bumper’s splitter. An absolute unit, as the British say.

WHAT IT WANTS: The first time you drive a ZR1 on a track, maybe a lap or three for feel, you will climb out of it and think, Well.

It is entirely possible that you will wonder if the car is broken. Because it is exceedingly, gloriously, brain-warpingly fast, which you knew. But something is different. Maybe it’s the small and dark cabin; it might be how the rear wheels are inches from your spine, or the light-switch torque and the occasionally off-putting body undulations while you’re howling through some corner in fourth gear and restrained by only a three-point belt.

Make no mistake: the ZR1 doesn’t just hand out laps. That’s partly why it’s great—you bring your A-game, or else. But it is also the kind of device that gives people like your author pause in a 130-mph corner, because he is prone to internal discussions with himself whenever his amygdala has much to think about. And the ZR1 gives you much to think about.

Modern Corvettes are complexity designed to feel simple. The variable-locking differential and active magnetorheological shocks, both digitally tied to the rest of the car, seem to work in concert, tweaking themselves just enough so you notice their behavior changing, but not so much that you worry about it. The quick, accurate steering is communicative but not a fountain of feedback. Every lap, those unflappable brakes are there, talkative and seemingly unkillable. Corners mean a late trail of the pedal, then sniffing out how much throttle the car will stand. It feels old-school and tomorrow-science at once. So you zero in on squeezing entry speed from the nose, and you try to not look at the speedometer, because that’s just consequences. You sweat a lot.

The Chevy regularly reminds you of your own mortality, which is fitting, as no one effectively wheels a ZR1 without a brain full of cold and clinical murder. This can be terrifying if you don’t try to listen to the car. Work up to its talents, however, and you’ll eventually find yourself driving around with stability control off—all Batman’s Joker, evil grin a mile wide, wondering why the illegal bits of life are so flippin’ illegal.

THE PRO SAID: “Feels more violent than the stock car. And out of everything here, the most like it’s threatening to bite—constantly telling you, ‘No, don’t do that. You’re going too far.’ But it’s incredible. And the brakes! You’re braking a marker and a half later than in the stock car, doing 130 mph. So much of a lap is just learning how much they have.

“The gearbox is a mess—I’d rather have a manual. There are a couple more shifts I’d like to make that I can’t, simply because the transmission can’t keep up. And the car can get a little edgy on corner entry; more stability there might be nice. But it’s relatively easy on the tires—you just have to keep from overheating the rears. The last couple tenths are fun but a lot of work.”

INTIMIDATING? Yes. The car always feels like it’s tolerating you. (Can we answer again? Yes.)

WHO BUYS IT? Sunday-cruise gentlemen of a certain age and speed limit. Chevrolet collectors obsessed with garage queens. And the true believers, those genius few, who just want to make local track-day guys cry.

2019 KTM X-BOW Comp R Limited Edition

For years, the rest of the world enjoyed the carbon-fiber wonder that is the KTM X-Bow while America went without. KTM Sportscar has been building the X-Bow with partners Dallara, Audi, and Magna since 2008, churning out some 1200 examples in that time. But the car couldn’t be had in the U.S. until 2018. That’s when the EPA finally agreed to allow the X-Bow in, on the condition that it remain a track-only vehicle. No picking up the kid from daycare in this thing.

A team of just 48 workers assembles the lightweight, mid-engine car in the KTM manufacturing facility near Graz, Austria. The Comp R DSG is the newest member of the fleet. It produces 295 hp from an Audi-sourced turbo- charged 2.0-liter four-cylinder engine bolted to a six-speed dual-clutch gearbox. And, thanks to its carbon-intense construction, the Comp R weighs less than 1900 pounds, without fuel. All of that’s good for a sub-four-second 0–60-mph sprint.

Limited Edition trim turns up the whole thing even further. There are the obvious changes, like the new aerodynamic bits and five-lug wheels, but the big news is the increase in engine output, to 346 hp. That’s accomplished via a carbon-fiber air intake, new high-pressure fuel pump, and a reflash. Adjustable anti-roll bars, adjustable brake balance, a specific race suspension, and a high-flow water pump are also part of the package. – Zach Bowman

PLACE OF ORIGIN: Austria, Land of Frivolity

LAYOUT: Mid-engine, rear-wheel drive; 2.0-liter turbocharged I-4, 346 hp, 321 lb-ft; six-speed twin-clutch sequential automatic

WEIGHT: 1900 lb (est)

0–60 MPH: 3.3 seconds (est)

¼-MILE: 11.1 seconds

PRICE: $104,450 base

NICKNAMES GIVEN BY R&T STAFF: Alien Sex Toy, Young Schwarzenegger, the Styrian Oak

THE BLUEPRINT: A Formula 3 car with a wider cockpit and a passenger seat. A Caterham Seven from space. Mid-engine, lots of tire and grip, immense suspension adjustability, no stability control or antilock brakes or anything that so much as resembles a driver aid. The X-Bow’s tub is a carbon monocoque with pushrod A-arm suspension and crash structures in a carbon-aluminum sandwich. Its structure was co-engineered by Dallara, the chassis provider for IndyCar. The car comes factory-equipped with Michelin slicks and isn’t street-legal. Just in case you didn’t think the people behind it were serious. (It’s Austrian. What else would you think?)

WHAT YOU GET: The X-Bow has been around since 2008, but the car first came to America in 2018, in track-focused, 295-hp Comp R form. The Comp R Limited Edition gets further hot-rodding, with an additional 51 hp, more downforce, a more track-oriented underfloor, and competition upgrades on everything from the water pump to the car’s cooling system and intercooler. Just 10 examples will be sold. (That said, you can build a Limited Edition from a base Comp R; most of the former’s fun bits come from KTM’s Power Parts factory catalog.)

The Audi-sourced turbo four-cylinder offers a grumbly exhaust and a torque band that wanes several hundred rpm before redline. The six-speed sequential twin-clutch, also from Audi, behaves like a road-car transmission because it is. KTM used borrowed parts here because the dirt-bike company’s car division is small and the X-Bow is its only product. The car looks like it, in the best way. Or maybe it’s just a formula car that some happy lunatic rolled through a pile of dirt-bike parts. Proper.

WHAT IT WANTS: First, a moment of digression for tires: the base X-Bow, sold in Europe, is shipped on road rubber. The Comp R and Limited Edition are effectively the same car, just faster and recalibrated for a purebred race tire.

Tires can drastically change a car, and the KTM is no exception. On road rubber, where it has more power than grip, an X-Bow is a drifty, manic pile of yaw and work. Road tires don’t mind sliding, and sliding is fun, so you lean into it. Add downforce, big spring and damper, and a relatively hard racing tire—the X-Bow’s S8L Michelin was designed for heavier production cars—and you enter another world. It’s like baking, where there’s only one answer to the math: if you don’t give the car exactly the right ingredients, it will eye you funny and then kick loose as if it had some inner need to bury itself in a wall.

The KTM isn’t fighting you, just particular. The slicks make almost no grip when cold and take at least half a lap of precise abuse to wake up. Once warm, they want a hair-thin window of slip and pathologically tidy hands. The Audi 2.0-liter four faucets out so much turbo lag as to occasionally light the rear tires over undulating pavement; the car takes sharp hands in a slide, and you either minimize those moments or risk cooking the Michelins.

This is all standard race-car stuff, and kind of the point. The KTM wants you to be a scientist, especially on the brakes, and if you don’t focus on high-resolution inputs, you’re slow. Much of the X-Bow’s speed comes on corner entry, turn-in straining your neck. There’s no windshield, so bugs smack into your skin and leave welts. That tiny wheel is heavy, the brakes consistent but long in travel, and the pedal mushy. The front suspension rockers sit exposed in front of the windshield, twitching in corners.

Simple is an understatement. The word “neutral” is too obvious. It’s fun as monkeys but also out for blood. That blood doesn’t have to be yours, but the car is getting it, one way or another, so you might as well be the one pulling the trigger.

THE PRO SAID: “It’s an impressive race car, and that’s what it is—a race car. When I climb in, I close my brain’s road-car file and open the one for open-wheelers. Get the tires up to temp, really work them. There’s noticeable downforce. The only trick is, the brake pedal can make it hard to be laser-accurate—most open-wheelers, the pedal is like a brick. I suspect they did that to help ordinary drivers get comfortable.

“Race cars are like that. Ninety percent of the people who buy these things will take time to figure what the car wants. The pros separate themselves from the pack in that zone—where you’re unsure is where they know.”

INTIMIDATING? Probably. But you’re too distracted by all the yelling in your helmet to care.

WHO BUYS IT? Anyone who takes life seriously. Anyone who lives by the words of the Greek philosopher Proclus, who said, “Wherever there is number, there is beauty.”

2019 NASCAR Toyota Camry Monster Energy Cup

PLACE OF ORIGIN: The Grand Old American South (Gaunt Brothers Racing, Mooresville, NC)

LAYOUT: Front-engine, rear-wheel drive; 5.9-liter V-8, 850 hp, more than 500 lb-ft; 4-speed manual

WEIGHT: 3300 lb

0–60 MPH: varies with gearing

¼-MILE: varies with gearing

PRICE: $75,000 (est)

NICKNAMES GIVEN BY R&T STAFF: Stock Boy, the Thrilla from Mooresville-a, Fatty the Wonder Truck

THE BLUEPRINT: A heavy, simple tube-frame platform never sold to the public but crafted as to make you think that bits of it might have been. A solid, locking rear axle located by components that NASCAR calls “truck arms,” because decades ago, their kinematics were borrowed from a pickup truck. Front suspension evolved from a ’66 Chevelle. An 8000-rpm pushrod V-8 that makes all the thunder-yawp in America. Disc brakes, not that you’d notice. Rear tires smaller than the ZR1’s fronts. Zero downforce.

Plus, in this example, a passenger seat. Perfect for deafening friends and spouses!

WHAT YOU GET: Stock cars mostly live on ovals, but properly calibrated, they can be made to turn left and right. Kligerman’s team, Gaunt Brothers Racing, occasionally assembles lightly used stock-car parts into track-day specials. The one we borrowed costs around $75,000. It wore a muffler for our test at Atlanta Motorsports Park but will bellow, uncorked, at around 130 decibels. Save a quiet exhaust and a few other touches, it’s basically a 2019 Cup car.

WHAT IT WANTS: Earplugs. Also delicacy, but in strange ways.

It is impossible to get into a stock car through the door, because there is no door. So you slide in the window feeling like Jimmie and Dale and Richard and Junior. The roll cage is a nest of chrome-moly bars named after driver crashes. (Petty Bar, Earnhardt Bar, Bodine Bar, and so on.) The driver’s legs are split by a large piece of padding called a knee-knocker, and the roof has vent flaps, to help keep the car on its wheels if you spin it at a buck fifty.

This stuff makes you feel safe. Light the engine and nail it in a straight line, you feel slightly more vulnerable. It’s such a strange mix of cautious and giddy that you want to get out of the car and laugh. The engine is a steamroller-cannon dynamite-grunt fireball that gives torque everywhere but rips hardest at high rpm and revs as if its crankshaft were made of air. It feels deeply purebred and fussed over. It was likely bolted under the hood with the help of a whip and a chair.

Everything else in the car is strangely not enough. Not enough brake or tire, not enough rear grip, not enough turning, not enough visibility. The differential governs the entire car. It will only unlock following a big throttle lift and a pause, and before it does, the car is going straight, no argument. (This is also why stock cars don’t like trail braking.) Once the rear locks again, the tires—we tested on a Goodyear slick similar to what NASCAR runs at its Sonoma road-course race—are so purposely overtaxed that a single corner’s abuse can send them off, overheated, and they’ll never come back.

The brake pedal is hard, high and only vaguely practical. If you use it too much, it will get closer to the floor and be even less useful and give you the creeping willies every time you step on it. The steering wheel sits in your lap, heavily boosted and feathery. You can turn the car on a finger, but feel is out to lunch.

In spite of all these factors, the car is a professional’s tool, and it spotlights talent. Nothing else here feels as much like it needs you. There is no friendly. Compromise is nonexistent. Abuse is everywhere. You spend the first lap wondering if you should have ever climbed in to begin with. Your body hurts when you’re done. It’s love.

THE PRO SAID: “Like driving a dump truck through a shopping mall. I can only get full throttle a few places—the car just won’t hook up. It wants to be unleashed, but you just can’t. You’re constantly asking it to do what it doesn’t want to do. The whole of modern NASCAR engineering exists to turn these beasts into prototypes—using Formula 1–level technology to gain tiny advantages, making the cars work better in places they shouldn’t.

“It’s so much fun. You’re sliding around, fighting to hook up the rears. If you bought one of these things, it’d force you to become very smooth—to learn what overhustle is. You are the fail-safe. You have to have a lot of respect for the car all the way up to the limit. At the end of the day, you feel integral.”

INTIMIDATING? Depends. Answer this: if you were attacked by a bear, and you happened to be holding a large knife, would you (a) use the knife, (b) throw down the knife and run, or (c) put the knife in your teeth and fight with your bare hands, because humans were meant to compete for dominance in their natural state? Any answer but C, this might not be your bag.

WHO BUYS IT? People who don’t care about stereotypes. People who care too much about stereotypes. And red-blooded, fire-breathing Americans who want, more than anything, to dance.

WHAT IS INTIMIDATING? If this test is any guide, the truth lies in Kligerman’s insight: fast cars that don’t always do what you want. Machines that need you to apply some jazz to their works. In the GT-R, that means fighting mass and thrust. In the Corvette, it’s grappling a road car with more power than a dying star and tires like ice. The KTM demands you play by its rules, and the Cup car is the Corvette free of manners. Or brakes.

In short, this stuff is what you make it. It’s not easy to learn the language of these cannons, but it’s not impossible, either. Their flaws make them great—and twice as satisfying when you do something right, because you had to work for it.

Unless you’re trying to flat-foot a ZR1 over a triple-digit crest with stability control off. Then you’re flying by the seat of your pants. Take a deep breath and pray a little, because landing there is a little bit you and a little bit, in old NASCAR parlance, talkin’ with the baby Jesus. We wouldn’t have it any other way.

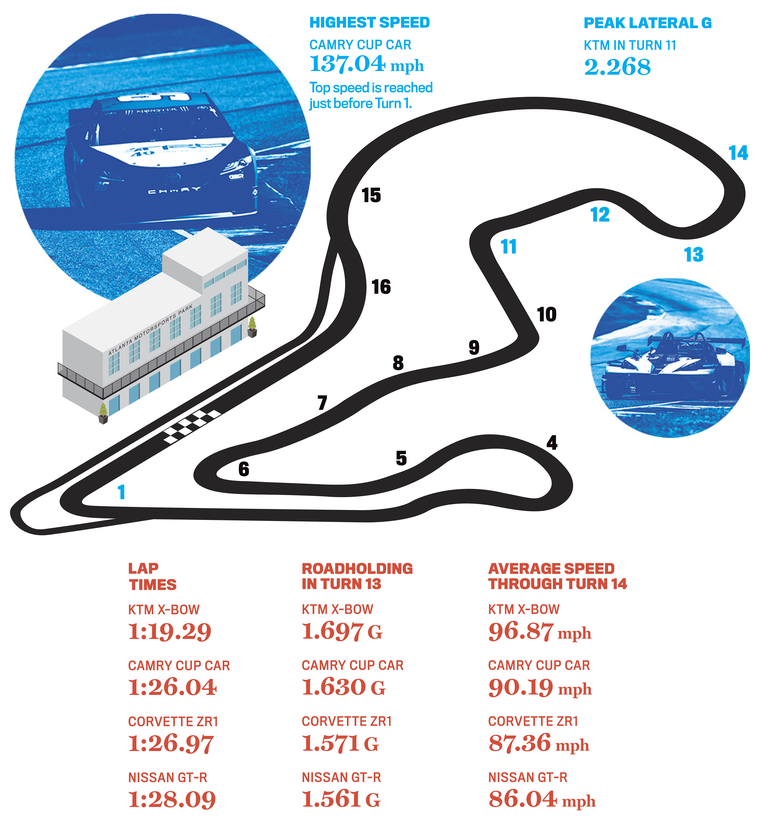

ATLANTA MOTORSPORTS PARK

Dawsonville, Georgia, is no stranger to racing. Home of NASCAR legend Bill Elliott, the tiny town an hour north of Atlanta lives and breathes the sport. It’s also where you’ll find Atlanta Motorsports Park. The main road course is two miles long, with 16 turns and 98 feet of rolling elevation change.

Designed by Hermann Tilke, the German engineer responsible for overhauling courses like the Nürburgring, Hockenheim, and Fuji Speedway, among others, AMP is a busy track. It caters to nimble, balanced cars, rather than high-horsepower bruisers, which helps explain why the KTM X-Bow walked away from its more musclebound competition.

AMP features an impressive, separate kart track, as well as a Radical Racing School with half-day, one-day, and three-day classes. Opt for the three-day, pay close attention, and there’s a good chance you’ll leave with a competition license.

TURN 1

Tight, downhill left-hander long acceleration run. The braking zone is shorter than it looks. Most cars pile into this and feel bound up, then released; it’s never natural, but the corner rewards patience and delicacy on throttle. Huge time to be gained here in how you come off the brakes and how you trim understeer down to the apex.

TURNS 2-14

Uphill, another climb, then a drop. Twelve and 13 ask the car to do several things at once—braking, turning, climbing, falling—all with large amounts of steering input and change, all while trying to accelerate. The combination punishes high curb weight, and the whole point is getting set up for a good run off 13, down the hill. If you’re smart, you rein in the car through 12 and 13, resisting the urge to abuse the front tires and keeping the nose under it to set up for 14. There isn’t a vehicle on earth that will feel settled through this combo, but that’s what makes it fun.

Who The Hell is Parker Kilgerman?

There’s a long list of professional drivers we could have turned to for a test like this, but few fill the bill like Parker Kligerman. The 28-year-old Connecticut native grew up car obsessed, poring over Speedvision race reruns and pestering his parents for a shot in a kart. But unlike most of us, he made good, his early talent shining through in a stack of wins that eventually culminated in a Formula Renault championship title.

In 2008, he found his way to stock cars through the ARCA series and the Penske driver-development program, driving in a couple of races for Cunningham Motorsports. The next year, Kligerman went full-time and pulled down a second-place points finish in his rookie season. Since then, he’s been everywhere and raced everything. He now splits his time between NASCAR starts with Gaunt Brothers Racing and announcing for NBC’s NASCAR America.

We figured Kligerman would be perfect to hustle the Camry and our other test cars around AMP. More important, however, he came to our test without the sponsor ties common to NASCAR drivers—he isn’t wedded to any manufacturer, and he isn’t a cardboard cutout regurgitating spoonfed lines.

“I’m very lucky,” he says. “I’m fortunate to be doing something that allows me to play with cars. They’re my passion. I always joke that I do TV and race just to fund my car obsession.”

In other words, Kligerman lives and breathes internal combustion. One of us. – Zach Bowman